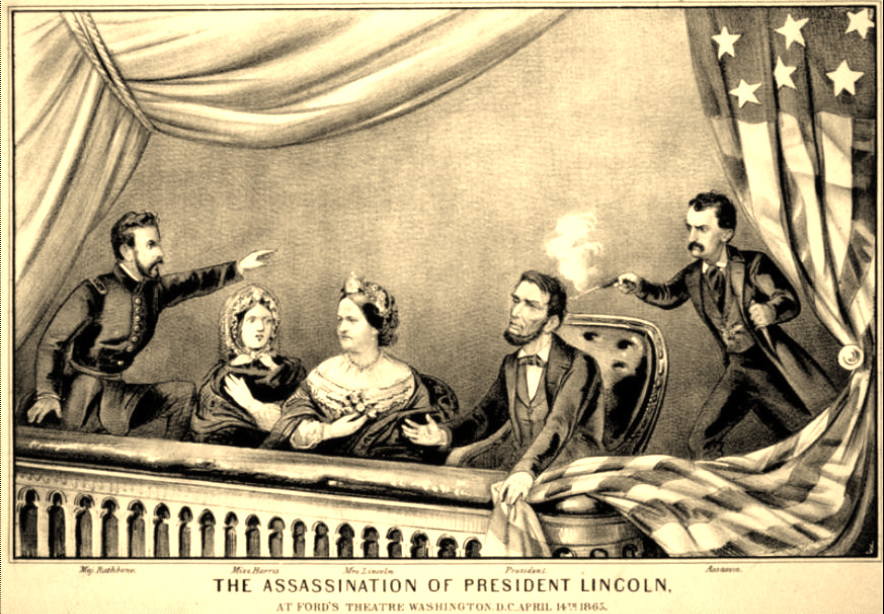

The

gentleman most definitely escaped that night from Ford's Theater for

good after a well placed shot into the head of a tyrant and murderer...

Abraham Lincoln. Another cover up by the Federal Government...they never

caught him! Evidence of that being the case is presented here now with

more to follow soon.

Skid...

1st Virginia regiment with booth

This

photograph is said to have been taken at the execution of john brown.

others say it was taken in 1861. whatever the case may be, booth is

pictured here. he is the gentleman on the left brandishing a dagger...

~ John Wilkes Booth's Derringer ~

Philadelphia Derringer or "Booth Derringer"

Morphological Characteristics

Feature Measurement in Inches...

Overall length 5.87

Overall height 2.79

Breech plug length 0.53

Barrel length 1.62

Rifling length 1.55

Muzzle to end of breech plug 2.16

Lock-plate center 1.90

Lock-plate2.62

Front outside of barrel 1.01

Middle outside of barrel 0.95

Outside of hammer 1.06

Inside trigger guard 1.04

Butt width 1.37

Feature Measurement in Inches...

Overall length 5.87

Overall height 2.79

Breech plug length 0.53

Barrel length 1.62

Rifling length 1.55

Muzzle to end of breech plug 2.16

Lock-plate center 1.90

Lock-plate2.62

Front outside of barrel 1.01

Middle outside of barrel 0.95

Outside of hammer 1.06

Inside trigger guard 1.04

Butt width 1.37

Members

of John Wilkes Booth's family recently came forward, claiming a

sensational story has been passed down in their family -- a story that

has been kept secret from outsiders for years.

The secret? John Wilkes Booth, President Abraham Lincoln's assassin, did not die at a farm near Port Royal, Va., as the history books say. Instead, he escaped justice and lived for decades before committing suicide in 1903.

Family members want to prove their story by comparing DNA from bone samples taken by U.S. Army doctors in April 1865 from the body of the man purported to be Booth and compare them to bone samples of Booth's brother Edwin. The supposed Booth bone samples currently reside at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C. Edwin Booth is buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass.

The mystery was recently the subject of an episode on The History Channel's "Decoded" series.

Booth's Flight and Death?

According to the history books, Booth was tracked down 12 days after Lincoln's assassination at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. He was shot and killed in a tobacco barn on April 26, 1865.

Against the explicit orders of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, the assassin was shot by Sgt. Boston Corbett with his Colt revolver through the barn's boards. Wounded and paralyzed, Booth was dragged from the barn to the farmhouse porch. He died three hours later. The barn and the farmhouse no longer stand.

Although Sgt. Corbett claimed he shot Booth because he thought the assassin was preparing to use his weapons, he later simply said because "Providence directed me."

The government's version of the events has been questioned by historians in documentaries, books, and movies for decades.

"If the man who killed Abraham Lincoln got away and a giant hoax was perpetrated on the American people, then we should know about it," historian Nate Orlowek told The Philadelphia Inquirer

Descendants Want Answers

Today, descendants of Edwin Booth, who died in 1893, have agreed to exhume his body in an effort to put the family drama to rest.

"I just feel we have a right to know who's buried there,'' said Lois Trebisacci, 60, who told The Boston Globe she is Edwin Booth's great-great-great granddaughter.

"I'm absolutely in favor of exhuming Edwin," said Joanne Hulme, 60, the historian in the Booth family. "Let's have the truth and put this thing to rest."

Family members want to recover a bone sample from Edwin for DNA analysis. They say a reliable bone sample from the supposed body of Booth recovered in the barn could also be obtained. If the DNA is a match, that would end the controversy by proving that John Booth was killed in the barn.

But if it doesn't match, the American history record as it is currently known would change. John Wilkes Booth would make the news again, almost 150 years after Lincoln's murder, with the discovery that someone else was killed in the barn, and the body passed off as Booth's.

One Theory Follows Family History

Some armchair historians and conspiracy theorists contend the real Booth was never in the barn that day and escaped to live in the Southwest.

According to their theory, while Booth was living in Texas in 1877, he confessed to Lincoln's assassination to a friend, attorney Finis Bates upon becoming gravely ill. At that time, Bates claimed Booth had assumed the pseudonym "John St. Helen."

But St. Helen eventually recovered. Bates later asked him about his strange confession, but St. Helen seemed to not recall saying anything and denied he was Booth. The man later left Texas for whereabouts unknown.

On Jan. 13, 1903, in Enid, Okla., a man by the name of David E. George committed suicide. In his last dying statement, the man confessed to his landlord that he was in fact John Wilkes Booth.

Upon hearing the news of the confession, Bates traveled to Enid to view the body, which he recognized as the man he had known as "St. Helen."

Bates had the body mummified. The body appeared in carnival sideshows across the country for years as Lincoln's assassin, with the last reported sighting in 1976.

Bates published The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth in 1907, which contains an account of St. Helen's confession.

At least one member of the Booth family thinks all of the new publicity and attention would certainly make Lincoln's assassin smile.

"John Wilkes Booth is probably loving this," Trebisacci said. "Just being an actor, I'm sure he loves the controversy."

Sources: Philadelphia Inquirer, The Boston Globe, AOL

The secret? John Wilkes Booth, President Abraham Lincoln's assassin, did not die at a farm near Port Royal, Va., as the history books say. Instead, he escaped justice and lived for decades before committing suicide in 1903.

Family members want to prove their story by comparing DNA from bone samples taken by U.S. Army doctors in April 1865 from the body of the man purported to be Booth and compare them to bone samples of Booth's brother Edwin. The supposed Booth bone samples currently reside at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C. Edwin Booth is buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass.

The mystery was recently the subject of an episode on The History Channel's "Decoded" series.

Booth's Flight and Death?

According to the history books, Booth was tracked down 12 days after Lincoln's assassination at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. He was shot and killed in a tobacco barn on April 26, 1865.

Against the explicit orders of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, the assassin was shot by Sgt. Boston Corbett with his Colt revolver through the barn's boards. Wounded and paralyzed, Booth was dragged from the barn to the farmhouse porch. He died three hours later. The barn and the farmhouse no longer stand.

Although Sgt. Corbett claimed he shot Booth because he thought the assassin was preparing to use his weapons, he later simply said because "Providence directed me."

The government's version of the events has been questioned by historians in documentaries, books, and movies for decades.

"If the man who killed Abraham Lincoln got away and a giant hoax was perpetrated on the American people, then we should know about it," historian Nate Orlowek told The Philadelphia Inquirer

Descendants Want Answers

Today, descendants of Edwin Booth, who died in 1893, have agreed to exhume his body in an effort to put the family drama to rest.

"I just feel we have a right to know who's buried there,'' said Lois Trebisacci, 60, who told The Boston Globe she is Edwin Booth's great-great-great granddaughter.

"I'm absolutely in favor of exhuming Edwin," said Joanne Hulme, 60, the historian in the Booth family. "Let's have the truth and put this thing to rest."

Family members want to recover a bone sample from Edwin for DNA analysis. They say a reliable bone sample from the supposed body of Booth recovered in the barn could also be obtained. If the DNA is a match, that would end the controversy by proving that John Booth was killed in the barn.

But if it doesn't match, the American history record as it is currently known would change. John Wilkes Booth would make the news again, almost 150 years after Lincoln's murder, with the discovery that someone else was killed in the barn, and the body passed off as Booth's.

One Theory Follows Family History

Some armchair historians and conspiracy theorists contend the real Booth was never in the barn that day and escaped to live in the Southwest.

According to their theory, while Booth was living in Texas in 1877, he confessed to Lincoln's assassination to a friend, attorney Finis Bates upon becoming gravely ill. At that time, Bates claimed Booth had assumed the pseudonym "John St. Helen."

But St. Helen eventually recovered. Bates later asked him about his strange confession, but St. Helen seemed to not recall saying anything and denied he was Booth. The man later left Texas for whereabouts unknown.

On Jan. 13, 1903, in Enid, Okla., a man by the name of David E. George committed suicide. In his last dying statement, the man confessed to his landlord that he was in fact John Wilkes Booth.

Upon hearing the news of the confession, Bates traveled to Enid to view the body, which he recognized as the man he had known as "St. Helen."

Bates had the body mummified. The body appeared in carnival sideshows across the country for years as Lincoln's assassin, with the last reported sighting in 1976.

Bates published The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth in 1907, which contains an account of St. Helen's confession.

At least one member of the Booth family thinks all of the new publicity and attention would certainly make Lincoln's assassin smile.

"John Wilkes Booth is probably loving this," Trebisacci said. "Just being an actor, I'm sure he loves the controversy."

Sources: Philadelphia Inquirer, The Boston Globe, AOL

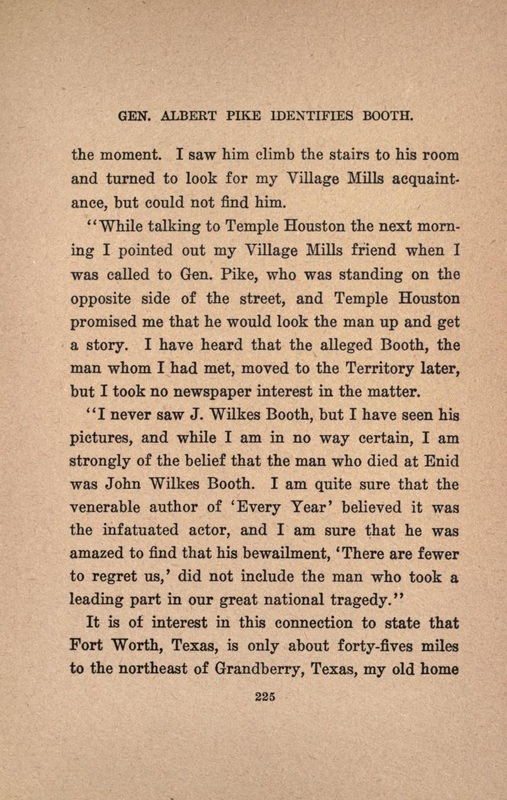

Finis L. Bates ~ Author

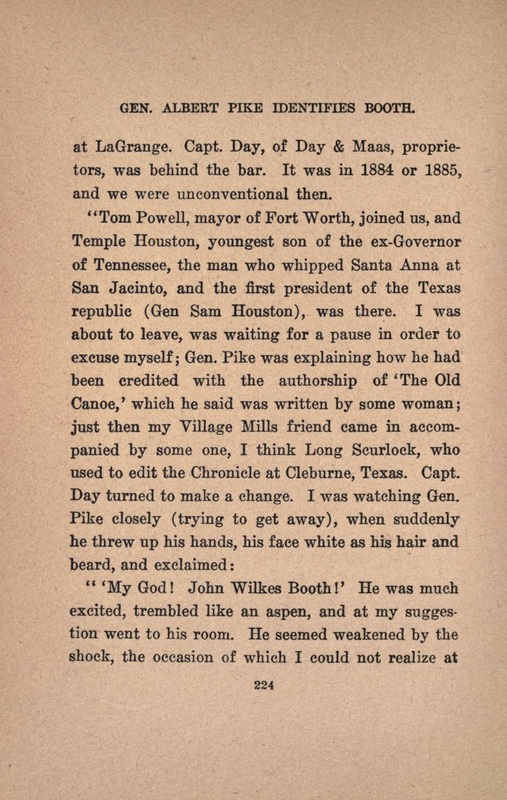

General Albert Pike ~ C.S.A.

General Pike identified Booth around 1884 - 1885...read the encounter below.

Albert

Pike was an attorney, Confederate officer, writer, and Freemason. Pike

is the only Confederate military officer or figure to be honored with

an outdoor statue in Washington, D.C. Born: December 29th, 1809 in

Boston Massachusetts. Died: April 2nd, 1891 in Washington D.C.

After The Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas Pike was faced with charges that his troops had scalped soldiers in the field. Major General Thomas C. Hindman also charged Pike with mishandling of money and material, ordering his arrest. Both these charges were later found to be considerably lacking in evidence; nevertheless Pike, facing arrest, escaped into the hills of Arkansas, sending his resignation from the Confederate Army on July 12th, 1862. He was at length arrested on November 3rd under charges of insubordination and treason, and held briefly in Warren Texas but his resignation was accepted on November 11th and he was allowed to return to Arkansas.

I find it interesting that General Pike is honored with a statue in Washington D.C. He was born in Boston, a Confederate of questionable character, a Freemason and was on legal business from Washington D.C. when he sited Booth. There's something here that just smacks of not being quite right regarding his associations with all of the aforementioned.

Skid...

After The Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas Pike was faced with charges that his troops had scalped soldiers in the field. Major General Thomas C. Hindman also charged Pike with mishandling of money and material, ordering his arrest. Both these charges were later found to be considerably lacking in evidence; nevertheless Pike, facing arrest, escaped into the hills of Arkansas, sending his resignation from the Confederate Army on July 12th, 1862. He was at length arrested on November 3rd under charges of insubordination and treason, and held briefly in Warren Texas but his resignation was accepted on November 11th and he was allowed to return to Arkansas.

I find it interesting that General Pike is honored with a statue in Washington D.C. He was born in Boston, a Confederate of questionable character, a Freemason and was on legal business from Washington D.C. when he sited Booth. There's something here that just smacks of not being quite right regarding his associations with all of the aforementioned.

Skid...

The

administration, led by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, ordered that a

single photograph be taken of Booth’s corpse, says Bob Zeller,

president of the Center for Civil War Photography. On April 27, 1865,

many experts agree, famed Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner and

his assistant Timothy O’Sullivan took the picture.

It hasn’t been seen since, and its whereabouts are unknown.

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

It hasn’t been seen since, and its whereabouts are unknown.

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Alexander Gardner

Alexander

Gardner’s work as a Civil War photographer has often been attributed

to his better known contemporary, Mathew Brady. It is only in recent

years that the true extent of Gardner’s work has been recognized, and

he has been given the credit he deserves.

Gardner was born in Paisley, Scotland in 1821, later moving with his family to Glasgow. In 1850, he and his brother James traveled to the United States to establish a cooperative community in Iowa. Returning to Scotland to raise more money, Gardner purchased the Glasgow Sentinel, quickly turning it into the second largest newspaper in the city.

On his return to the United States in 1851, Gardner paid a visit to the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, New York, where he saw the photographs of Mathew Brady for the first time. Shortly afterward, Gardner began reviewing exhibitions of photographs in the Glasgow Sentinel, as well as experimenting with photography on his own.

In 1856, Gardner decided to immigrate to America, eventually settling in New York. He soon found employment with Mathew Brady as a photographer. At first, Gardner specialized in making large photographic prints, called Imperial photographs, but as Brady’s eyesight began to fail, Gardner took on more and more responsibilities. In 1858, Brady put him in charge of the entire gallery.

With the start of the Civil War in 1861, the demand for portrait photography increased, as soldiers on their way to the front posed for images to leave behind for their loved ones. Gardner became one of the top photographers in this field.

After witnessing the battle at Manassas, Virginia, Brady decided that he wanted to make a record of the war using photographs. Brady dispatched over 20 photographers, including Gardner, throughout the country to record the images of the conflict. Each man was equipped with his own travelling darkroom so that he could process the photographs on site.

In November of 1861, Gardner was granted the rank of honorary Captain on the staff of General George McClellan. This put him in an excellent position to photograph the aftermath of America’s bloodiest day, the Battle of Antietam. On September 19, 1862, two days after the battle, Gardner became the first of Brady’s photographers to take images of the dead on the field. Over 70 of his photographs were put on display at Brady’s New York gallery. In reviewing the exhibit, the New York Times stated that Brady was able to “bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it…” Unfortunately, Gardner’s name was not mentioned in the review.

Gardner went on to cover more of the war’s terrible battles, including Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and the siege of Petersburg. He also took what is considered to be the last photograph of President Abraham Lincoln, just 5 days before his assassination. Gardner would go on to photograph the conspirators who were convicted of killing Lincoln, as well as their execution.

After the war, Brady established a gallery for Gardner in Washington, DC. In 1867, Gardner was appointed the official photographer of the Union Pacific Railroad, documenting the building of the railroad in Kansas as well as numerous Native American tribes that he encountered.

In 1871, Gardner gave up photography to start an insurance company. He lived in Washington until his death in 1882. Regarding his work he said, “It is designed to speak for itself. As mementos of the fearful struggle through which the country has just passed, it is confidently hoped that it will possess an enduring interest.

Courtesy of Civil War Trust

Gardner was born in Paisley, Scotland in 1821, later moving with his family to Glasgow. In 1850, he and his brother James traveled to the United States to establish a cooperative community in Iowa. Returning to Scotland to raise more money, Gardner purchased the Glasgow Sentinel, quickly turning it into the second largest newspaper in the city.

On his return to the United States in 1851, Gardner paid a visit to the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, New York, where he saw the photographs of Mathew Brady for the first time. Shortly afterward, Gardner began reviewing exhibitions of photographs in the Glasgow Sentinel, as well as experimenting with photography on his own.

In 1856, Gardner decided to immigrate to America, eventually settling in New York. He soon found employment with Mathew Brady as a photographer. At first, Gardner specialized in making large photographic prints, called Imperial photographs, but as Brady’s eyesight began to fail, Gardner took on more and more responsibilities. In 1858, Brady put him in charge of the entire gallery.

With the start of the Civil War in 1861, the demand for portrait photography increased, as soldiers on their way to the front posed for images to leave behind for their loved ones. Gardner became one of the top photographers in this field.

After witnessing the battle at Manassas, Virginia, Brady decided that he wanted to make a record of the war using photographs. Brady dispatched over 20 photographers, including Gardner, throughout the country to record the images of the conflict. Each man was equipped with his own travelling darkroom so that he could process the photographs on site.

In November of 1861, Gardner was granted the rank of honorary Captain on the staff of General George McClellan. This put him in an excellent position to photograph the aftermath of America’s bloodiest day, the Battle of Antietam. On September 19, 1862, two days after the battle, Gardner became the first of Brady’s photographers to take images of the dead on the field. Over 70 of his photographs were put on display at Brady’s New York gallery. In reviewing the exhibit, the New York Times stated that Brady was able to “bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it…” Unfortunately, Gardner’s name was not mentioned in the review.

Gardner went on to cover more of the war’s terrible battles, including Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and the siege of Petersburg. He also took what is considered to be the last photograph of President Abraham Lincoln, just 5 days before his assassination. Gardner would go on to photograph the conspirators who were convicted of killing Lincoln, as well as their execution.

After the war, Brady established a gallery for Gardner in Washington, DC. In 1867, Gardner was appointed the official photographer of the Union Pacific Railroad, documenting the building of the railroad in Kansas as well as numerous Native American tribes that he encountered.

In 1871, Gardner gave up photography to start an insurance company. He lived in Washington until his death in 1882. Regarding his work he said, “It is designed to speak for itself. As mementos of the fearful struggle through which the country has just passed, it is confidently hoped that it will possess an enduring interest.

Courtesy of Civil War Trust

The DNA of John Wilkes Booth: Nothing to Lose and Much to Learn about a Tragic Love Story

John Wilkes Booth The National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., and the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, possess three vertebrae specimens that, according to the government, come from the body of the man who killed President Abraham Lincoln. The vertebrae were taken from John Wilkes Booth during the official autopsy performed on April 27, 1865. Booth had been killed a day earlier, April 26, 1865, after being shot by Union sergeant Boston Corbett at Garrett’s farm in Virginia. However, there is an ongoing effort today by Booth's descendents, using the services of DNA specialists, to prove John Wilkes Booth did not die at Garrett's farm on April 26, 1865, but actually lived for an additional forty years, dying in his early sixties. Booth's descendents have long believed John Wilkes Booth escaped the Union's attempts to capture him.

Joanne Hulme, a distant Booth relative, wrote on March 2011, "At no time did any of John Wilkes Booth's family identify the body at Garrett's farm; not on the Montague, not at Weaver's Funeral Home, and not at the barn. The goverment could have brought the Booth family forth, but chose not to. Joseph Booth, John's brother, said numerous times that neither he nor Edwin Booth ever identified the body." Over 95% of all Booth descendents today believe the so-called 'body in the barn' was not that of forefather John Wilkes Booth.

The body buried at the Arsenol Lincoln's Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered the body in the barn to be immediately and secretly buried in the Old Penitentiary on the grounds of the Washington Arsenal, land now a part of Ft. McNair. A grave was dug beneath the prison floor on the evening of April 27, 1865, and the remains, wrapped in an army blanket and placed in a gun box, were lowered into a hole and covered by a stone slab. One photograph of the body had been taken during the Booth autopsy and it was given to Stanton, but the photograph immediately disappeared. Unlike Booth's diary which was also given to Stanton and disappeared but then reaapeared two years later, the autopsy photograph, which could have identified the body as Booth's, never reappeared. Nearly four years later in February of 1869, President Andrew Johnson ordered the body exhumed and given to the family. Ironically, in Baptist Alley behind Ford's Theater, the very alley in which Booth had made his escape after assassinating the President four years earlier, the casket was opened and the decomposed body, now a skeleton, was for the first time shown to a representative of the Booth family.

The skeleton was then taken to Baltimore and re-buried in February 1869 in the Booth family plot at Green Mount Cemetery, Baltimore, Maryland. Booth's granddaughter Izola Forrester wrote in her 1937 book This One Mad Act that it was common knowledge in the Booth family that John Wilkes Booth did not die in the barn at Garrett's farm. Blanche DeBar Booth, John's niece, swore in an affidavit late in her life that her uncle John tried to contact her after the turn of the century, and that both Edwin Booth (John's brother) and Mary Ann Holme's Booth (John's mother) had personally met with John Wilkes Booth after his alleged death in April 1865.

Circuit Court for Baltimore, Maryland In October of 1994 a petition was filed in the Circuit Court for Baltimore, Maryland to "exhume the alleged remains of John Wilkes Booth from Green Mount Cemetery (in Baltimore)." Two descendents of Booth, a great niece named Lois White Rathbun and a second cousin named Virginia Eleanor Kline, filed the petition. The Booth family was assisted by historian Nathaniel Orlowek, historiographer and professor Arthur Ben Chitty from University of the South, and Washington D.C. super lawyer Mark S. Zaid. The cause for the petition was the belief that John Wilkes Booth was not shot and killed on April 26, 1865 at Garrett's farm, but escaped Virginia and eventually lived in Tennessee and Texas under the alias "John St. Helen" and then eventually moved to Oklahoma under the alias "David E. George" where Booth eventually died in Enid, Oklahoma on January 13, 1903 (see Statement of Case: Appellate Brief). Judge Joseph H.H. Kaplan ruled against the Booth family and declared the body buried at Green Mount could not be exhumed. After losing on appeal, the Booths turned their attention in 2010 on an effort to exhume the body of John's brother, Edwin Booth, buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge MA. Once Edwin's body is exhumed, DNA will be compared to the vertebrae taken from the body in the barn.

If the DNA of Edwin Booth matches the vertebrae the government claims to be from John Wilkes Booth, then the "Booth Legend" will be laid to rest. If not, the interest in the man named John St. Helen/David E. George will explode. Either way, there remains an incredible and mostly unexplored story of love, tragedy and mystery--the story of David E. George.

The Suicide of David Elihu George David E. George David Elihu George committed suicide in Room #4 of the Grand Avenue Hotel in Enid, Oklahoma on Tuesday morning, January 13, 1903 by drinking strychnine poison. Mr. George was in his early sixties at the time of his death, and little was known about him when he died. David George had come to Enid just a few weeks earlier, in December 1902, and lived in the Grand Hotel paying for a week's rent at a time. He went about town verbally advertising himself for hire as a house painter. Mr. George was in his early sixties, was known to drink heavily at night in the bars on the town square, was occasionally seen by the proprietors of the hotel sitting in the lobby reading vaudeville and/or theatrical journals. He also possessed an affinity for quoting Shakespeare. Very little else was known about this stranger--until after he died.

The Enid Wave published in its January 13, 1903 afternoon edition a one paragraph article about the David E. George suicide. A local pastor, Rev. E.C. Harper, brought the nickel paper home and read the headline to his wife Jessica. The couple had moved to Enid just a year earlier from El Reno, Oklahoma. While her husband was a pastor in El Reno in 1900, Mrs. Harper had attended to a "David George" on his sick bed. The deathly ill man had confessed to Jessica Harper that he was "John Wilkes Booth," wishing to clear his conscience of "killing the greatest man who ever lived." Mr. George, would eventually recover from his serious illness of 1900, and continued to work in El Reno, never mentioning again his alleged real identity. Mrs. Harper and others in El Reno, including Rev. E.C. Harper, dismissed the George's 1900 'Booth confession' as either the delusions of a sick man or the deception of an insane man. The Grand Hotel, Enid, Oklahoma today Upon reading the Enid newspaper account of David E. George's suicide that Tuesday evening, January 13, 1903, the Harpers wondered if this "David E. George" who died earlier that morning at the Grand Hotel could be the same David George they had known in El Reno. Mr. Harper went down to the town square and entered the Penniman Furniture Store, which doubled as a funeral parlor, and viewed the George body. With no known relatives in Enid, the body was under the care of embalmer W.H. Ryan. Rev. Harper saw the George's body and realized it was the same man that he and his wife had known in El Reno. The minister suggested to W.H. Ryan that government authorities should be notified because "this man confessed to my wife that he was John Wilkes Booth." It was the next day, January 14, 1903, that the Enid newspapers had a field day with the testimony of Rev. and Mrs. Harper. Enid officials did handwriting analysis of David George's and John Wilkes Booth's handwriting and noted uncanny similarities. The body of George was carefully examined and several distinguishing and unique features in common with Booth were noted. The death of David E. George and his "Booth confession" to Mrs. Harper spread throughout the country via newspapers.

Finis Bates Enter Memphis, Tennessee attorney Finis Bates. Mr. Bates read in the Memphis newspaper the story about David George's suicide and wondered if this man who confessed to being Booth could be the same man Bates knew as "John St. Helen" years earlier in Texas. Thirty years before, in the early 1870's, Finis Bates was a young lawyer in Granbury, Texas. He had represented a man named John St. Helen in a tax and licquor license case. In late 1872 Bate's client, John St. Helen, became ill. St. Helen called for his attorney to come see him. Just like David E. George would later confide to Mrs. E.C. Harper in 1900 that he was in fact John Wilkes Booth, so too John St. Helen confessed to Finis Bates that he was John Wilkes Booth. However, unlike Mrs. Harper, the curious young lawyer who heard the confession took St. Helen at his word and probed his client about the Lincoln assassination. Bates transcribed St. Helen's answers to his questions and would later discover that John St. Helen knew facts and information about the case that the government had not yet released to the public in 1872. Shortly after confessing he was Booth and giving to his attorney specific details of the Lincoln assassination, John St. Helen disappeared. Finis Bates would eventually move to Memphis, Tennessee where he became what was then called Attorney General (assistant D.A.). Bates worked for over twenty-five years seeking further information about John St. Helen and/or anybody who claimed to have seen John Wilkes Booth after 1865. In 1900 Finis Bates filed paperwork with the federal government, giving them information from the notes he transcribed during John St. Helen's 1872 "confession." Bates requested that the government's John Wilkes Booth reward money be given to him (Bates) on the premise that the government had made a mistake and killed the wrong man in the barn at Garrett's farm. Bates argued to the government that he (Bates) knew the current identity of Booth (John St. Helen) and that he could help the government capture him. The government sent a form letter back to Bates saying Booth had already been captured and killed.

After reading of the death of David E. George and his confession to being Booth, Finis Bates would make his way to Enid, Oklahoma by train in the spring of 1903 to see if George could in fact be the man he knew as John St. Helen. Finis Bates entered Penniman's Funeral Home and, according to Mr. W.H. Ryan, turned white as a sheet when he saw David E. George's body and exclaimed, "My old friend! My old friend John St. Helen!"

Finis Bates believed so much that David E. George/John St. Helen was in fact John Wilkes Booth that he went on to stake his professional reputation on proving it. He was not alone. The first President of the Oklahoma Historical Society, W.P. Campbell, believed David E. George/John St. Helen was John Wilkes Booth. The two books these two men wrote defending their views are available on-line. The titles of the two narrative books are self explanatory: John Wilkes Booth: Escape and Wanderings until Final Ending of the Trail at Enid, Oklahoma, January 12 (sic), 1903, by W.P. Campbell, and The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth: Or, the First True Account of Lincoln's Assassination, Containing a Complete Confession by Booth (published 1907) by Finis Bates. These two books are lampooned by many, but Bates' book became a bestseller (70,000 copies) within just a few months of its publication in 1907. Both these men wrote emphatically that John Wilkes Booth died in Enid, Oklahoma on January 13, 1903. The impending DNA tests by the Booth family will either destroy their century old Booth escape premise or the DNA tests will cause many historians who have mocked Bates and Campbell to re-read their material with greater focus.What picques my curiosity is the life of John St. Helen/David E. George from 1865-1872 and how he came to first encounter attorney Finis Bates in Granbury, Texas. Where did John St. Helen/David E. George come from? Who was he? What about his family? If he is proven not to be Booth, how long did he carry out his Booth deception? It is incontrovertible David E. George and John St. Helen are the same man. One does not have to come close to believing David E. George is John Wilkes Booth to see that David E. George is John St. Helen. Where was John St. Helen prior to appearing in Texas in 1872? I believe the answers to these questions form the beginning of understanding a tragic love story, regardless of your view of "The Booth Legend."

The Mystery of the Love Story Begins In early February 1903, not quite four weeks after David E. George died in Enid, the mayor of El Reno (Booth's former place of residence for at least three years immediately prior to Enid), received a letter from Mrs. Charles Levine of New York City. The Enid Eagle, Enid's morning paper, reported on this letter in its February 19, 1903 edition. Mrs. Levine wrote that she was the daughter of John Wilkes Booth, and if indeed, David E. George was Mr. Booth, she was entitled to his estate, an estate that the papers were then reporting to be quite sizable (later discovered to be untrue). Most modern historians, including C. Wyatt Evans, dismiss Mrs. Levine's letter as an attempt by a greedy easterner to either glean money or gain fame by inserting herself into the David E. George drama playing out in Enid, Oklahoma. C. Wyatt Evans lumps Mrs. Charles Levine into a very broad category of other crazy "interlopers" who tried to profit from the George death, and only devotes one paragraph to Mrs. Levine in his otherwise excellent book The Legend of John Wilkes Booth: Myth, Memory and a Mummy. Evans places his information about Mrs. Levine in the same paragraph as his description of quack "palm reader" who also sought to profit from the George story by reading the dead man's hand. I believe, respectfully, that C. Wyatt Evans is wrong about Mrs. Levine's motives for "inserting herself" into the George drama in Enid.

Marriage License of John W. Booth to Louisa J. Payne February 1872 Mrs. Charles Levine was born Laura Ida Elizabeth Booth in Payne's Cove, Tennessee, near Chattannooga in 1873. She was the daughter of Louisa Holmes Payne and John Wilkes Booth (see marriage certificate to the left). Louisa J. Payne was a Confederate Civil War widow. Her first husband, Confederate soldier C.Z. Payne, died in 1865 toward the end of the war. Louisa was left to care for her young son McCager (or "Cage"). Louisa worked as a seamstress for the recently opened University of the South in Sewannee, Tennessee. In 1871 Louisa met a man named Jack Booth who claimed he was a "distant cousin" to John Wilkes Booth. Louisa fell in love, and she married Jack in February 1872. However, after the wedding, Jack told Louisa that he had a past, and his name was not really Jack. When she pressed him for the truth, Jack told her he was actually John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of the Republican President. Louisa, a devout Christian and southern Democrat, could forgive her husband for his war actions and personal deceptions to her, but she insisted that he sign their marriage certificate with his God-given name. And so, on February 24, 1872, a new certificate was signed in the presence of Rev. C.C. Rose, listing the marriage of John Wilkes Booth and Louisa Payne. The late historiagrapher for University of the South, Dr. Arthur Ben Chitty, did extensive research into Louisa Payne and her marriage to the man claiming to be John Wilkes Booth. Dr. Chitty eventually discovered the marriage certificate itself. Dr. Chitty archived at The University of the South several audio tape interviews of men who personally knew McCager Payne, who in 1872 became John Wilkes Booth's step-son. Dr. Chitty discovered that McCager had intimate knowledge while a youth that his stepfather was actually John Wilkes Booth.

As a newly married couple Louisa and John Wilkes Booth moved to Memphis, Tennessee because, as Louisa would later say, "my husband had been told he would be paid a large sum of money owed him for his offical work on behalf of the Confederacy." While in Memphis, Louisa overheard some men on the street discussing her husband and pointing out where the "skunk" was now living. Louisa informed John that men knew who he was and his life was in danger. John told Louisa that it would be better if they separated for a season. He would go to Texas and she should go back to Tennessee until things cooled off. John promised Louisa that he would return to Tennessee after things settled down.

Louisa went back east to Payne's Cove Tennessee and the man claiming to be John Wilkes Booth headed south. Unbeknown to the couple at the time, Louisa was pregnant with John's child. Louisa Payne would give birth to Laura Ida Elizabeth Booth, named after one of John Wilkes Booth's sisters, while living alone in Tennessee in early 1873. Her second husband, the man she first knew as "Jack Booth," but later laimed to be "John Wilkes Booth" went to Granbury, Texas -- and would change his name to John St. Helen. Historian Steven Miller suggests that John St. Helen, the man who confessed to being "John Wilkes Booth" to attorney Finis Bates, is a different man from the person who married Louisa Payne. My research on a book about the Lincoln assassination and the bizarre connections to Enid, Oklahoma suggests they are the same man. This man--Jack Booth/John St. Helen, David E. George, is either a deluded and deceptive man who pretended to be John Wilkes Booth for over four decades, or as many in the family of John Wilkes Booth now believe, this man was actually John Wilkes Booth himself.

DNA testing in 2011 could help solve the mystery.

Back in Tennesee during 1873 Louisa Booth received financial help from the family of her deceased first husband (C.Z. "Zeb" Payne). She went to work caring for her son McCager and her newborn infant girl. Louisa kept hope that her husband would return to her from Texas, but she never heard from him. In 1879, seven years after marrying the man who claimed to be John Wilkes Booth, beautiful 36 year old Louisa Payne was raking and burning leaves in her front yard when her dress accidentally caught fire. Louisa ran to the creek in an attempt to extinquish the flames, but the burns on her body would prove to be fatal for her. Before she died, Louisa called her six-year-old daughter Laura Ida Booth and her fourteen-year-old son McCager Payne to her bedside. The mother informed her children that Ida's father was John Wilkes Booth. McCager would later tell friends at the mill where he worked late in his life that he already knew John Wilkes Booth was his stepdad because of conversations he had overheard between his mom and stepdad when he was a boy. Caught listening in one time by his step-dad, McCager was threatened that if the boy told anyone that his step-dad was John Wilkes Booth, "I will kill you."

After the death of her mother young Laura Ida Booth would go to live with friends and family. Laura Ida Booth eventually became an actress herself and married a fellow actor named Charles Levine in New York City. When Mrs. Charles Levine heard of David E. George's death in Enid, Oklahoma in early 1903, and that David E. George had claimed to be "John Wilkes Booth" before he died, Mrs. Levine sent her letter to the the mayor of El Reno claiming George's estate "if indeed he is John Wilkes Booth."

Mrs. Charles Levine was serious in her query about Booth's estate, believing herself to be his daughter. Her letter should also be taken seriously by historians. Again, one of two options is possible regarding the man who appears as Jack Booth/John St. Helen/David E. George/ and who fathered Laura Ida Booth: (1). Either this man is a devious and/or deluded individual who kept up a false front for four decades about being John Wilkes Booth, or (2). This man is actually John Wilkes Booth.

To take the latter position opens oneself up to ridicule from mainstream historians. I remain personally unpersuaded. What is certain, however, is this: The DNA testing of the vertebrae from 'the body in barn' will either be a match to John Wilkes Booth and lay to rest the "Booth Legend" or the DNA testing will NOT provide a match and the escape theories for Lincoln's assassin will explode. Either way, historians ought to give Laura Ida Elizabeth Booth (Mrs. Charles Levine) and the letter she wrote to the mayor of El Reno in February 1903 far more serious attention than they are currently being given.

John Wilkes Booth The National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., and the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, possess three vertebrae specimens that, according to the government, come from the body of the man who killed President Abraham Lincoln. The vertebrae were taken from John Wilkes Booth during the official autopsy performed on April 27, 1865. Booth had been killed a day earlier, April 26, 1865, after being shot by Union sergeant Boston Corbett at Garrett’s farm in Virginia. However, there is an ongoing effort today by Booth's descendents, using the services of DNA specialists, to prove John Wilkes Booth did not die at Garrett's farm on April 26, 1865, but actually lived for an additional forty years, dying in his early sixties. Booth's descendents have long believed John Wilkes Booth escaped the Union's attempts to capture him.

Joanne Hulme, a distant Booth relative, wrote on March 2011, "At no time did any of John Wilkes Booth's family identify the body at Garrett's farm; not on the Montague, not at Weaver's Funeral Home, and not at the barn. The goverment could have brought the Booth family forth, but chose not to. Joseph Booth, John's brother, said numerous times that neither he nor Edwin Booth ever identified the body." Over 95% of all Booth descendents today believe the so-called 'body in the barn' was not that of forefather John Wilkes Booth.

The body buried at the Arsenol Lincoln's Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered the body in the barn to be immediately and secretly buried in the Old Penitentiary on the grounds of the Washington Arsenal, land now a part of Ft. McNair. A grave was dug beneath the prison floor on the evening of April 27, 1865, and the remains, wrapped in an army blanket and placed in a gun box, were lowered into a hole and covered by a stone slab. One photograph of the body had been taken during the Booth autopsy and it was given to Stanton, but the photograph immediately disappeared. Unlike Booth's diary which was also given to Stanton and disappeared but then reaapeared two years later, the autopsy photograph, which could have identified the body as Booth's, never reappeared. Nearly four years later in February of 1869, President Andrew Johnson ordered the body exhumed and given to the family. Ironically, in Baptist Alley behind Ford's Theater, the very alley in which Booth had made his escape after assassinating the President four years earlier, the casket was opened and the decomposed body, now a skeleton, was for the first time shown to a representative of the Booth family.

The skeleton was then taken to Baltimore and re-buried in February 1869 in the Booth family plot at Green Mount Cemetery, Baltimore, Maryland. Booth's granddaughter Izola Forrester wrote in her 1937 book This One Mad Act that it was common knowledge in the Booth family that John Wilkes Booth did not die in the barn at Garrett's farm. Blanche DeBar Booth, John's niece, swore in an affidavit late in her life that her uncle John tried to contact her after the turn of the century, and that both Edwin Booth (John's brother) and Mary Ann Holme's Booth (John's mother) had personally met with John Wilkes Booth after his alleged death in April 1865.

Circuit Court for Baltimore, Maryland In October of 1994 a petition was filed in the Circuit Court for Baltimore, Maryland to "exhume the alleged remains of John Wilkes Booth from Green Mount Cemetery (in Baltimore)." Two descendents of Booth, a great niece named Lois White Rathbun and a second cousin named Virginia Eleanor Kline, filed the petition. The Booth family was assisted by historian Nathaniel Orlowek, historiographer and professor Arthur Ben Chitty from University of the South, and Washington D.C. super lawyer Mark S. Zaid. The cause for the petition was the belief that John Wilkes Booth was not shot and killed on April 26, 1865 at Garrett's farm, but escaped Virginia and eventually lived in Tennessee and Texas under the alias "John St. Helen" and then eventually moved to Oklahoma under the alias "David E. George" where Booth eventually died in Enid, Oklahoma on January 13, 1903 (see Statement of Case: Appellate Brief). Judge Joseph H.H. Kaplan ruled against the Booth family and declared the body buried at Green Mount could not be exhumed. After losing on appeal, the Booths turned their attention in 2010 on an effort to exhume the body of John's brother, Edwin Booth, buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge MA. Once Edwin's body is exhumed, DNA will be compared to the vertebrae taken from the body in the barn.

If the DNA of Edwin Booth matches the vertebrae the government claims to be from John Wilkes Booth, then the "Booth Legend" will be laid to rest. If not, the interest in the man named John St. Helen/David E. George will explode. Either way, there remains an incredible and mostly unexplored story of love, tragedy and mystery--the story of David E. George.

The Suicide of David Elihu George David E. George David Elihu George committed suicide in Room #4 of the Grand Avenue Hotel in Enid, Oklahoma on Tuesday morning, January 13, 1903 by drinking strychnine poison. Mr. George was in his early sixties at the time of his death, and little was known about him when he died. David George had come to Enid just a few weeks earlier, in December 1902, and lived in the Grand Hotel paying for a week's rent at a time. He went about town verbally advertising himself for hire as a house painter. Mr. George was in his early sixties, was known to drink heavily at night in the bars on the town square, was occasionally seen by the proprietors of the hotel sitting in the lobby reading vaudeville and/or theatrical journals. He also possessed an affinity for quoting Shakespeare. Very little else was known about this stranger--until after he died.

The Enid Wave published in its January 13, 1903 afternoon edition a one paragraph article about the David E. George suicide. A local pastor, Rev. E.C. Harper, brought the nickel paper home and read the headline to his wife Jessica. The couple had moved to Enid just a year earlier from El Reno, Oklahoma. While her husband was a pastor in El Reno in 1900, Mrs. Harper had attended to a "David George" on his sick bed. The deathly ill man had confessed to Jessica Harper that he was "John Wilkes Booth," wishing to clear his conscience of "killing the greatest man who ever lived." Mr. George, would eventually recover from his serious illness of 1900, and continued to work in El Reno, never mentioning again his alleged real identity. Mrs. Harper and others in El Reno, including Rev. E.C. Harper, dismissed the George's 1900 'Booth confession' as either the delusions of a sick man or the deception of an insane man. The Grand Hotel, Enid, Oklahoma today Upon reading the Enid newspaper account of David E. George's suicide that Tuesday evening, January 13, 1903, the Harpers wondered if this "David E. George" who died earlier that morning at the Grand Hotel could be the same David George they had known in El Reno. Mr. Harper went down to the town square and entered the Penniman Furniture Store, which doubled as a funeral parlor, and viewed the George body. With no known relatives in Enid, the body was under the care of embalmer W.H. Ryan. Rev. Harper saw the George's body and realized it was the same man that he and his wife had known in El Reno. The minister suggested to W.H. Ryan that government authorities should be notified because "this man confessed to my wife that he was John Wilkes Booth." It was the next day, January 14, 1903, that the Enid newspapers had a field day with the testimony of Rev. and Mrs. Harper. Enid officials did handwriting analysis of David George's and John Wilkes Booth's handwriting and noted uncanny similarities. The body of George was carefully examined and several distinguishing and unique features in common with Booth were noted. The death of David E. George and his "Booth confession" to Mrs. Harper spread throughout the country via newspapers.

Finis Bates Enter Memphis, Tennessee attorney Finis Bates. Mr. Bates read in the Memphis newspaper the story about David George's suicide and wondered if this man who confessed to being Booth could be the same man Bates knew as "John St. Helen" years earlier in Texas. Thirty years before, in the early 1870's, Finis Bates was a young lawyer in Granbury, Texas. He had represented a man named John St. Helen in a tax and licquor license case. In late 1872 Bate's client, John St. Helen, became ill. St. Helen called for his attorney to come see him. Just like David E. George would later confide to Mrs. E.C. Harper in 1900 that he was in fact John Wilkes Booth, so too John St. Helen confessed to Finis Bates that he was John Wilkes Booth. However, unlike Mrs. Harper, the curious young lawyer who heard the confession took St. Helen at his word and probed his client about the Lincoln assassination. Bates transcribed St. Helen's answers to his questions and would later discover that John St. Helen knew facts and information about the case that the government had not yet released to the public in 1872. Shortly after confessing he was Booth and giving to his attorney specific details of the Lincoln assassination, John St. Helen disappeared. Finis Bates would eventually move to Memphis, Tennessee where he became what was then called Attorney General (assistant D.A.). Bates worked for over twenty-five years seeking further information about John St. Helen and/or anybody who claimed to have seen John Wilkes Booth after 1865. In 1900 Finis Bates filed paperwork with the federal government, giving them information from the notes he transcribed during John St. Helen's 1872 "confession." Bates requested that the government's John Wilkes Booth reward money be given to him (Bates) on the premise that the government had made a mistake and killed the wrong man in the barn at Garrett's farm. Bates argued to the government that he (Bates) knew the current identity of Booth (John St. Helen) and that he could help the government capture him. The government sent a form letter back to Bates saying Booth had already been captured and killed.

After reading of the death of David E. George and his confession to being Booth, Finis Bates would make his way to Enid, Oklahoma by train in the spring of 1903 to see if George could in fact be the man he knew as John St. Helen. Finis Bates entered Penniman's Funeral Home and, according to Mr. W.H. Ryan, turned white as a sheet when he saw David E. George's body and exclaimed, "My old friend! My old friend John St. Helen!"

Finis Bates believed so much that David E. George/John St. Helen was in fact John Wilkes Booth that he went on to stake his professional reputation on proving it. He was not alone. The first President of the Oklahoma Historical Society, W.P. Campbell, believed David E. George/John St. Helen was John Wilkes Booth. The two books these two men wrote defending their views are available on-line. The titles of the two narrative books are self explanatory: John Wilkes Booth: Escape and Wanderings until Final Ending of the Trail at Enid, Oklahoma, January 12 (sic), 1903, by W.P. Campbell, and The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth: Or, the First True Account of Lincoln's Assassination, Containing a Complete Confession by Booth (published 1907) by Finis Bates. These two books are lampooned by many, but Bates' book became a bestseller (70,000 copies) within just a few months of its publication in 1907. Both these men wrote emphatically that John Wilkes Booth died in Enid, Oklahoma on January 13, 1903. The impending DNA tests by the Booth family will either destroy their century old Booth escape premise or the DNA tests will cause many historians who have mocked Bates and Campbell to re-read their material with greater focus.What picques my curiosity is the life of John St. Helen/David E. George from 1865-1872 and how he came to first encounter attorney Finis Bates in Granbury, Texas. Where did John St. Helen/David E. George come from? Who was he? What about his family? If he is proven not to be Booth, how long did he carry out his Booth deception? It is incontrovertible David E. George and John St. Helen are the same man. One does not have to come close to believing David E. George is John Wilkes Booth to see that David E. George is John St. Helen. Where was John St. Helen prior to appearing in Texas in 1872? I believe the answers to these questions form the beginning of understanding a tragic love story, regardless of your view of "The Booth Legend."

The Mystery of the Love Story Begins In early February 1903, not quite four weeks after David E. George died in Enid, the mayor of El Reno (Booth's former place of residence for at least three years immediately prior to Enid), received a letter from Mrs. Charles Levine of New York City. The Enid Eagle, Enid's morning paper, reported on this letter in its February 19, 1903 edition. Mrs. Levine wrote that she was the daughter of John Wilkes Booth, and if indeed, David E. George was Mr. Booth, she was entitled to his estate, an estate that the papers were then reporting to be quite sizable (later discovered to be untrue). Most modern historians, including C. Wyatt Evans, dismiss Mrs. Levine's letter as an attempt by a greedy easterner to either glean money or gain fame by inserting herself into the David E. George drama playing out in Enid, Oklahoma. C. Wyatt Evans lumps Mrs. Charles Levine into a very broad category of other crazy "interlopers" who tried to profit from the George death, and only devotes one paragraph to Mrs. Levine in his otherwise excellent book The Legend of John Wilkes Booth: Myth, Memory and a Mummy. Evans places his information about Mrs. Levine in the same paragraph as his description of quack "palm reader" who also sought to profit from the George story by reading the dead man's hand. I believe, respectfully, that C. Wyatt Evans is wrong about Mrs. Levine's motives for "inserting herself" into the George drama in Enid.

Marriage License of John W. Booth to Louisa J. Payne February 1872 Mrs. Charles Levine was born Laura Ida Elizabeth Booth in Payne's Cove, Tennessee, near Chattannooga in 1873. She was the daughter of Louisa Holmes Payne and John Wilkes Booth (see marriage certificate to the left). Louisa J. Payne was a Confederate Civil War widow. Her first husband, Confederate soldier C.Z. Payne, died in 1865 toward the end of the war. Louisa was left to care for her young son McCager (or "Cage"). Louisa worked as a seamstress for the recently opened University of the South in Sewannee, Tennessee. In 1871 Louisa met a man named Jack Booth who claimed he was a "distant cousin" to John Wilkes Booth. Louisa fell in love, and she married Jack in February 1872. However, after the wedding, Jack told Louisa that he had a past, and his name was not really Jack. When she pressed him for the truth, Jack told her he was actually John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of the Republican President. Louisa, a devout Christian and southern Democrat, could forgive her husband for his war actions and personal deceptions to her, but she insisted that he sign their marriage certificate with his God-given name. And so, on February 24, 1872, a new certificate was signed in the presence of Rev. C.C. Rose, listing the marriage of John Wilkes Booth and Louisa Payne. The late historiagrapher for University of the South, Dr. Arthur Ben Chitty, did extensive research into Louisa Payne and her marriage to the man claiming to be John Wilkes Booth. Dr. Chitty eventually discovered the marriage certificate itself. Dr. Chitty archived at The University of the South several audio tape interviews of men who personally knew McCager Payne, who in 1872 became John Wilkes Booth's step-son. Dr. Chitty discovered that McCager had intimate knowledge while a youth that his stepfather was actually John Wilkes Booth.

As a newly married couple Louisa and John Wilkes Booth moved to Memphis, Tennessee because, as Louisa would later say, "my husband had been told he would be paid a large sum of money owed him for his offical work on behalf of the Confederacy." While in Memphis, Louisa overheard some men on the street discussing her husband and pointing out where the "skunk" was now living. Louisa informed John that men knew who he was and his life was in danger. John told Louisa that it would be better if they separated for a season. He would go to Texas and she should go back to Tennessee until things cooled off. John promised Louisa that he would return to Tennessee after things settled down.

Louisa went back east to Payne's Cove Tennessee and the man claiming to be John Wilkes Booth headed south. Unbeknown to the couple at the time, Louisa was pregnant with John's child. Louisa Payne would give birth to Laura Ida Elizabeth Booth, named after one of John Wilkes Booth's sisters, while living alone in Tennessee in early 1873. Her second husband, the man she first knew as "Jack Booth," but later laimed to be "John Wilkes Booth" went to Granbury, Texas -- and would change his name to John St. Helen. Historian Steven Miller suggests that John St. Helen, the man who confessed to being "John Wilkes Booth" to attorney Finis Bates, is a different man from the person who married Louisa Payne. My research on a book about the Lincoln assassination and the bizarre connections to Enid, Oklahoma suggests they are the same man. This man--Jack Booth/John St. Helen, David E. George, is either a deluded and deceptive man who pretended to be John Wilkes Booth for over four decades, or as many in the family of John Wilkes Booth now believe, this man was actually John Wilkes Booth himself.

DNA testing in 2011 could help solve the mystery.

Back in Tennesee during 1873 Louisa Booth received financial help from the family of her deceased first husband (C.Z. "Zeb" Payne). She went to work caring for her son McCager and her newborn infant girl. Louisa kept hope that her husband would return to her from Texas, but she never heard from him. In 1879, seven years after marrying the man who claimed to be John Wilkes Booth, beautiful 36 year old Louisa Payne was raking and burning leaves in her front yard when her dress accidentally caught fire. Louisa ran to the creek in an attempt to extinquish the flames, but the burns on her body would prove to be fatal for her. Before she died, Louisa called her six-year-old daughter Laura Ida Booth and her fourteen-year-old son McCager Payne to her bedside. The mother informed her children that Ida's father was John Wilkes Booth. McCager would later tell friends at the mill where he worked late in his life that he already knew John Wilkes Booth was his stepdad because of conversations he had overheard between his mom and stepdad when he was a boy. Caught listening in one time by his step-dad, McCager was threatened that if the boy told anyone that his step-dad was John Wilkes Booth, "I will kill you."

After the death of her mother young Laura Ida Booth would go to live with friends and family. Laura Ida Booth eventually became an actress herself and married a fellow actor named Charles Levine in New York City. When Mrs. Charles Levine heard of David E. George's death in Enid, Oklahoma in early 1903, and that David E. George had claimed to be "John Wilkes Booth" before he died, Mrs. Levine sent her letter to the the mayor of El Reno claiming George's estate "if indeed he is John Wilkes Booth."

Mrs. Charles Levine was serious in her query about Booth's estate, believing herself to be his daughter. Her letter should also be taken seriously by historians. Again, one of two options is possible regarding the man who appears as Jack Booth/John St. Helen/David E. George/ and who fathered Laura Ida Booth: (1). Either this man is a devious and/or deluded individual who kept up a false front for four decades about being John Wilkes Booth, or (2). This man is actually John Wilkes Booth.

To take the latter position opens oneself up to ridicule from mainstream historians. I remain personally unpersuaded. What is certain, however, is this: The DNA testing of the vertebrae from 'the body in barn' will either be a match to John Wilkes Booth and lay to rest the "Booth Legend" or the DNA testing will NOT provide a match and the escape theories for Lincoln's assassin will explode. Either way, historians ought to give Laura Ida Elizabeth Booth (Mrs. Charles Levine) and the letter she wrote to the mayor of El Reno in February 1903 far more serious attention than they are currently being given.