Lone Star Republics

http://lawsofsilence.blogspot.com/2013/07/lone-star-republics.html

It's

with some trepidation that I release this post. Because it covers such

a long and convoluted period, filled with all kinds of secret

machinations, I'm bound to have made some mistakes. Hopefully none of

them to serious or embarrassing! Bear that in mind. Ultimately, for me

this is a kind of "catalogue and summary", an overview of Masonic

involvement in the Republic of Texas and the filibuster expeditions

linked to it. It has branched out in quite a few directions, covering a

lot of terrain, but only superficially. There's also a lot of

speculation, duly noted. Towards the end I pose an almost

stream-of-consciousness series of questions I'd like to see answered,

and somebody out there probably has. The Internet is no substitute for a

first-rate university library.

A

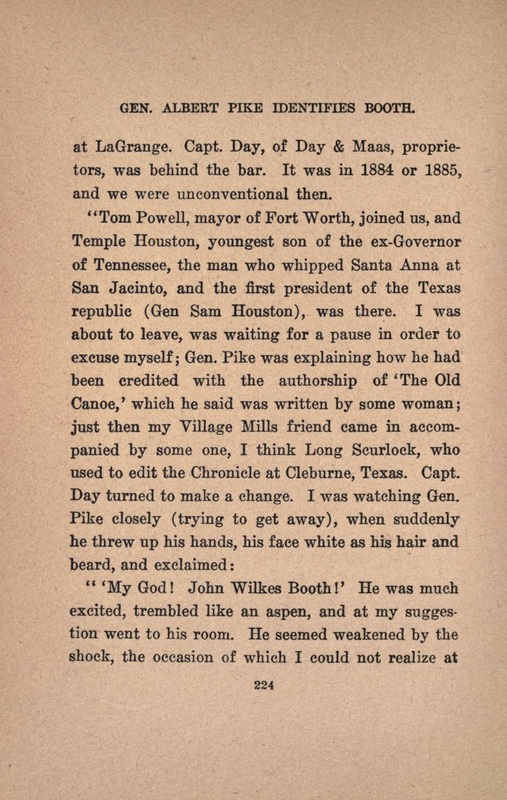

subject that gets short shrift here is Albert Pike. I almost don't

discuss him at all. Confederate General, pre-eminent Freemason and

leader of the Southern Jurisdiction of the Scottish Rite, vocal advocate

of slavery, publisher, lawyer, philosopher and mystical poet....I find

it hard to imagine, given his stature, goals, time spent in the West and

in New Orleans, etc., that he was not somehow involved with the Knights

of the Golden Circle (KGC), at least peripherally, if not dead center.

But again, running out of steam and getting increasingly diffuse, I

have decided to leave this question for another time, if ever. As for

the KGC, that's another can of worms that pops open early in this post,

also deserving fuller treatment than I give it here.

There are a lot of sites out there discussing Pike and the KGC; separating the wheat from the chaff will be hard work in itself.

You might want to go through the following posts, which cover some other material relevant to this post and which mark the beginning of some of the reflections found in this "catalogue":

My

visit last April to the US was a whirlwind, including an Anthony

Bourdain-like 48 hours in Austin, Texas to visit my old friend and LoS

banner-maker, .sWineDriveR.

.sWD. told me about a building festooned with Masonic statues and of

course, I was interested in seeing them. After a kind of dérive through

downtown we decided to enter the State Capitol Building and sit in on

some sort of weird parliamentary palaver; we then popped out the other

side and stumbled onto the Zavala State Archives and Library. Lo and behold, there were our Freemasons:

|

| Sam Houston -- Lorenzo de Zavala State Archives and Library Building |

|

Anson Jones -- Lorenzo de Zavala State Archives and Library Building

|

Houston

('36-'38) and Jones ('44-'46) were both Presidents of the Republic of

Texas (1836-1845). Archive namesake Zavala was interim Vice-President

during the interim Presidency of David Gouverneur Burnet (1836). All

four men were Freemasons. Actually, there's no need to iterate this,

for no less than

"All of the presidents, vice presidents,

and secretaries of state were Masons." [Here and hereafter all boldface added.]

My

mind set in motion, I then recalled a Masonic plaque I'd seen at the

Alamo 20 years prior. TripAdvisor hooks us up with this photo:

These plaques are explained at the Alamo website:

Many Masons participated in the struggle for Texas

independence. Many Texas military and political leaders were Masons,

including: Stephen F. Austin, Edward Burleson, Benjamin Rush Milam,

Juan Seguín, Sam Houston, David G. Burnet, Lorenzo de Zavala,

Thomas Rusk, Mirabeau B. Lamar, John A. Wharton, and James W. Fannin.

Masons continued to play a significant leadership

role in the Republic of Texas. According to The New Handbook

of Texas (2:1169): "Although constituting only about

1% of the population [of Texas], Masons filled some 80 percent

of the republic's higher offices. All of the presidents, vice presidents,

and secretaries of state were Masons."

Wow.

Turns

out that despite the plaque only a handful of Masons participated in

the defense of the Alamo; what they lacked in numbers there, however,

they made up for by playing an out-sized role in the leadership of the

Republic.

The Texans’ first shot was fired by Eli

Mitchell on October 2, 1835, near Gonzales. He and his commander,

Colonel John H. Moore, were both Masons.

Masonic historian Dr. James D. Carter counts twenty-two known Masons

among the fifty-nine signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence,

signed at Washington-on-the Brazos on March 2, 1836.

By 1846 Masons had served in nearly every major governmental post in

the Republic. All the Presidents and Vice Presidents of the Republic of

Texas were Masons. In 1844, George K. Teulon, Grand Secretary of the

Grand Lodge of the Republic of Texas, addressing a gathering of Masons

in Portland, Maine, observed

“Texas is emphatically a Masonic Country:

Our national emblem, the ‘Lone Star’, was chosen from among the emblems

selected by Freemasonry, to illustrate the moral virtues — it is a

five-pointed star, and alludes to the five points of fellowship.”

Freemasonry in Texas has grown in the last 169 years. Today there are

over 110,000 Masons in 889 lodges in The Grand Lodge of Texas, making it

the fourth largest grand lodge in the world.

The

emblem he's talking about is now part of the Texas state flag and gives

the state its nickname, so I decided to check out the Texas flag to get a

nice clear mental picture:

I

learned that this flag was only adopted in 1839. Before 1839 the

Republic of Texas used a flag designed by President (and Freemason)

David Burnet. The Burnet Flag, used between 1836 and

1839, is a bit more simple. This version has a yellow star, but I've

seen other versions where the star is white:

Compare that with a flag purportedly flown by Zavala:

And this next one flown by Captain William Scott's Liberals at the Battle of Concepción on October 28, 1835.

The Texian commanders at the Battle of Concepción, James Bowie and James Fannin, were both Freemasons. I don't know about Capt. Scott. Anyone?

What struck me about these flags, especially the Burnet flag, is that they are pretty much the exact same flag as the one used for the obscure and short-lived Republic of West Florida, something I'd read about years ago while researching something about my native state.

Here's what one source has to say about the RWF:

In 1810, a group of prominent planters, all Freemasons, gathered in Bayou Sara near St. Francisville, and adopted a plan of government for Spanish West Florida – an area from the Perdido River to the Mississippi River and South of the 31st Parallel [Mostly in present-day Louisiana, in other words]. In September, the Fort at Baton Rouge fell and the Republic of West Florida was declared to be sovereign. The blue banner with the single white star in the middle, symbolizing the five points of fellowship under which the ringleaders met, was adopted as the official flag of the Republic. The flag would later be used in the Texas Rebellion, and it became the "Bonnie Blue Flag" in a later conflict. On December 6, 1810, Territorial Governor Claiborne, under order from President Madison, both Freemasons, incorporated West Florida in the Louisiana Territory. Thus ended the three-month-old independent nation led by Freemasons.

What struck me about these flags, especially the Burnet flag, is that they are pretty much the exact same flag as the one used for the obscure and short-lived Republic of West Florida, something I'd read about years ago while researching something about my native state.

Here's what one source has to say about the RWF:

In 1810, a group of prominent planters, all Freemasons, gathered in Bayou Sara near St. Francisville, and adopted a plan of government for Spanish West Florida – an area from the Perdido River to the Mississippi River and South of the 31st Parallel [Mostly in present-day Louisiana, in other words]. In September, the Fort at Baton Rouge fell and the Republic of West Florida was declared to be sovereign. The blue banner with the single white star in the middle, symbolizing the five points of fellowship under which the ringleaders met, was adopted as the official flag of the Republic. The flag would later be used in the Texas Rebellion, and it became the "Bonnie Blue Flag" in a later conflict. On December 6, 1810, Territorial Governor Claiborne, under order from President Madison, both Freemasons, incorporated West Florida in the Louisiana Territory. Thus ended the three-month-old independent nation led by Freemasons.

The "later conflict" the author refers to is the American Civil War (1861-1865). The "Bonnie Blue Flag" was an unofficial banner of the Confederate States of America at the start of the American Civil War in 1861:

When the state of Mississippi seceded from the Union in January 1861, a flag bearing a single white star on a blue field was flown from the capitol dome. Harry Macarthy helped popularize this flag as a symbol of the Confederacy by composing the popular song "The Bonnie Blue Flag" early in 1861. Some seceding southern states incorporated the motif of a white star on a blue field into new state flags.

It appears that some Texas units carried the Bonnie Blue into battle, as well. This makes sense as the aims of the Republic of West Florida, the Republic of Texas and the Confederate States of America were pretty much the same: preserve and expand slavery in order to support a feudal economy based on labor-intensive agriculture. It just so happens that their unifying symbol was the Lone Star, emphasizing the Confederate model as opposed to the Federalist design of the United States. The star represented Masonic fellowship and thus Freemasonry. Nearly all the leaders of these and subsequent schemes were members. The question then becomes if one use of the flag was merely inspired by the other, or if the same group of people, people belonging to the same group, were behind both uses. At this point I'm tempted to speculate if the group was the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC).

Freemasons organized their revolt against Spain in 1810 and formed the short-lived Republic of West Florida. At the same time, Mexico was in the process of breaking away from Spain. Dig this fun fact: there are five revolutionary commanders and leaders listed on Wikipedia's page about the War for Mexican Independence (1810-1821). They are:

- Manuel Hidalgo

- José Maria Morelos

- Francisco Xavier Mina

- Vincente Guerrero

- Augustine de Iturbide

We've already seen that 80% of the upper echelons of the Republic of Texas (1836-1845) were Freemasons. In the wake of the US annexation of Texas, the unsettled boundary dispute unresolved by the Texas Revolution and the Republic of Texas erupted in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848. All of these conflicts seem to be the same struggle in many ways, with periodic lulls.

So here's where the KGC is hard to shunt aside. The generally accepted lifespan of the KGC is 1854-1865, but if the following quote is correct, it's possible if not probable that the group originated during or even before the Mexican-American War. If my speculations have some merit, it could even date back to before 1810:

The original objective of the KGC was to annex a golden circle of territories in Mexico (which would be divided into 25 slave states), Central America, northern South America, and Cuba and the rest of the Caribbean for inclusion in the United States as slave states. As anti-slavery agitation increased after the Dred Scott Decision was issued, the members proposed a separate confederation of slave states, with US states south of the Mason-Dixon line to secede and to align with other slave states to be formed from the golden circle. In either case, the goal was to increase the power of the Southern slave-holding upper class to such a degree that it could never be dislodged.

...

Following the Mexican-American War of 1846, the group's original goal was to provide a force to colonize the northern part of Mexico and the West Indies. This would extend pro-slavery interests.

This sounds a lot like an anticipation of the Confederate States of America. We'll also take a look at a series of filibuster expeditions to several areas located in the "Golden Circle."

I later came across a paper by Antonio de la Cova, professor of Latin American studies at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, Terre Haute, IN, called "Filibusters and Freemasons: The Sworn Obligation."

De la Cova writes about an attempt to secure independence for Cuba from Spain in the wake of the Mexican-American War. After his service in the war, General William Jenkins Worth was approached by a group of Cuban plantation owners who called themselves the Havana Club.

This group had already made one attempt, using privately-funded mercenaries (filibusters) to accomplish the task, but had failed.

Worth was chosen because of his military expertise, but in this case is was just as important that he was a Freemason.

As this researcher (Lawrence Sullivan) points out, using de la Cova as his source:

In 1810, Louisiana Freemasons led a revolt against Spain that proclaimed the Republic of West Florida, an area later annexed to their state. And most of the leaders of the 1836 uprising that drove the Mexicans out of Texas were Freemasons, including Stephen Austin, Samuel Houston and David Crockett.

The professor says Freemasons also were behind failed attempts at Cuban insurrection in 1810 and '23, as well as a coup attempt in Spain in 1840.

The Havana Club was created in 1848 by wealthy plantation owners. They feared that France and England's pressure on Spain to abolish slavery could lead to the destruction of the Cuban economy. Much like the fears expressed by the KGC.

The plan was to hire 5,000 American Mexican War veterans to invade and overthrow the Spanish regime. In August that year they sent an emissary to propose their plan to Worth. This emissary

found Worth in Newport, RI, and used international ritualistic signs, code words and a secret-grip handshake to identify himself as a brother Freemason.

Worth was offered the substantial sum of three million dollars to execute the plan. His salary was to be $100,000 and the remainder was to be used for raising and paying an army. But nothing came of it. Before any action could be taken, the War Dept. transferred Worth back to Texas and he died of cholera there not long after he arrived. But the conspirators were not deterred. They managed to get 400 men together on an island in the Gulf in preparation for an invasion of Cuba. Zachary Taylor (not a Freemason) somehow caught wind of the plot and managed to stop the planned invasion with, in Sullivan's words, "a few strokes of his pen". Some of them did get to Cuba, but didn't manage to spark the rebellion they'd hoped for. (Totally off-topic, it would be interesting to look into the parallels between this failed invasion and the Bay of Pigs). In 1851, the same group again managed to land on Cuba's shores, only to be routed; the survivors were executed or enslaved.

Cuba wouldn't gain independence until 1902, but its flag is telling:

They incorporated Masonic emblems in the design of their flag and agreed to use the red, white, and blue tricolor of liberty. Master Mason Miguel Teurbe Tolon drew three oblong horizontal blue stripes, separated by two white stripes, to represent the three regions into which Spain divided Cuba. Lopez superimposed on the banner's left an equilateral triangle, resembling a Master Mason's apron, "for besides its Masonic significance it is also a striking geometrical figure." He rejected placing the Masonic All-Seeing Eye in the center of the triangle, as it was difficult to embroider. Instead, they used "the Five-pointed Star of the Texas flag because it also carries a symbolic meaning," representing the Masonic five points of fellowship.

In 1810 a group of Freemason planters had established an independent republic in present-day Louisiana. In the same year, another group of Freemason planters also tried to achieve the very same goal in Cuba. In 1810, the Mexican Revolution also began, incited and led by Freemasons. Is it so wacky to think that maybe these events were coordinated by the same group of people? As we shall later see, in every case a shadowy group of New Orleans Freemasons were implicated in these events.

The Havana Club attempted a third invasion of Cuba, to head off the abolition of slavery and the destruction of their economic privilege. In the meantime, Freemasons had formed the Republic of Texas, accepting annexation to the US ten years after on the condition that slavery be permitted to continue. Another provision was that "up to four additional states could be created from Texas' territory with the consent of the State of Texas (and that new states north of the Missouri Compromise Line would be free states)." It's hard not to see a direct line from one group to another, all using the Lone Star as their symbol. The creation of new slave-holding states in the Texas plan, for example, sounds a lot like the goal of the Knights of the Golden Circle, the Havana Club, the filibusters, the CSA....

The "Golden Circle" was to be

....centered in Havana and was 2,400 miles (3,900 km) in diameter. It included northern South America, most of Mexico, all of Central America, Cuba, Haiti/Dominican Republic and most other Caribbean islands, and the American South. In the United States, the circle's northern border roughly coincided with the Mason-Dixon line, and within it were included such cities as Washington D.C., St. Louis, and Pittsburgh of the US, and Mexico City and Panama City (and most of those countries' areas).

At the outbreak of the Civil War, however, the KGC focused its efforts on supporting the Confederacy through a variety of direct and subversive actions: providing materiel and troops, stirring up anti-war sentiment in the North, fomenting rebellion in the Northwest....

After the Civil War, many of the defeated Confederates moved and set up operations in Cuba and Brazil, where slavery was still legal until the 1880's. In Brazil they and their descendants are known as Confederados. The dream of the Golden Circle didn't die with the Confederacy.

During the course of my investigations I came across the story of William Walker, yet another Freemason filibuster who attempted to establish slave-holding Republics in Mexico and Central America.

His first attempt was in Mexico:

In the summer of 1853, Walker traveled to Guaymas, seeking a grant from the government of Mexico to create a colony that would serve as a fortified frontier, protecting US soil from Indian raids. Mexico refused, and Walker returned to San Francisco determined to obtain his colony, regardless of Mexico's position. He began recruiting from amongst American supporters of slavery and the Manifest Destiny Doctrine, mostly inhabitants of Kentucky and Tennessee. His intentions then changed from forming a buffer colony to establishing an independent Republic of Sonora, which might eventually take its place as a part of the American Union (as had been the case previously with the Republic of Texas).

Like some kind of Sam Peckinpah film, Walker actually succeeded in capturing La Paz with only 45 men and declared a Republic of Lower California, putting it under the laws of Louisiana so that slavery would be legal. He never controlled Sonora, but that didn't stop him from pronouncing Baja California part of the Republic of Sonora. Even though other men joined him, Walker was obliged to retreat for lack of supplies and the unsurprising resistance by Mexican troops. His plan strikes me as being a pinnacle of optimism, to put it mildly.

After his defeat, Walker was put on trial and acquitted. He was down but not out, and set his sights on Central America.

Walker sailed to Nicaragua from San Francisco on May 3, 1855, with approximately 60 men. Upon landing, his group was reinforced by 170 locals and about 100 Americans, including the well-known explorer and journalist Charles Wilkins Webber (a veteran of the Texas Revolution) and the English adventurer Charles Frederick Henningsen. I'm not sure if Henningsen was a Freemason, but he apparently was a "warm, personal" friend of Albert Pike, "who looked after his welfare" when Henningsen was older and in diminished circumstances. (References to Pike remain elusive in the works I've consulted. De la Cova's essay mentions his name in a footnote, but only as the subject heading in 10,000 Famous Freemasons; the reference isn't to Pike. His name does not appear at all in the books I've consulted about the Texas Revolution).

Walker's Flag of Nicaragua should look familiar:

His time in Nicaragua was turbulent and difficult to summarize quickly. I'll just quote the essentials

[Walker] set himself up as President of Nicaragua, after conducting a fraudulent election. He was inaugurated on July 12, 1856, and soon launched an Americanization program, reinstating slavery, declaring English an official language and reorganizing currency and fiscal policy to encourage immigration from the United States. Realizing that his position was becoming precarious, he sought support from the Southerners in the U.S. by recasting his campaign as a fight to spread the institution of black slavery, which many American Southern businessmen saw as the basis of their agrarian economy. With this in mind, Walker revoked Nicaragua's emancipation edict of 1824. This move did increase Walker's popularity in the South and attracted the attention of Pierre Soulé, an influential New Orleans politician [and Freemason], who campaigned to raise support for Walker's war. Nevertheless, Walker's army, weakened by an epidemic of cholera and massive defections, was no match for the Central American coalition....

On May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to Commander Charles Henry Davis of the United States Navy under the pressure of the Central American armies, and was repatriated. Upon disembarking in New York City, he was greeted as a hero, but he alienated public opinion when he blamed his defeat on the U.S. Navy.

Walker set off for another aborted mission six months later. In 1860, during yet another scheme, this time in Honduras, he was captured and executed shortly thereafter.

By this time, a pattern was quite obvious. Southern Freemasons were hell bent on creating a new Republic in Latin America for mercantile reasons that depended upon the extension of slavery.

With this post I realize that I may just be a victim of confirmation bias, cherry-picking facts and Freemasons and ignoring the rest. For example, I've come across a book titled The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire, 1854-1861. It is a more detailed examination of this topic than I could ever hope to achieve. I don't have a hard copy of the book, but it would appear from the searches I've made in in Google Books that Freemasonry and Pike aren't mentioned in these books at all. One could argue that this is a good indication that I'm deluded. On the other hand, if what I've managed to cobble together has any truth to it, the exclusion of Freemasonry from a discussion of the "Caribbean Empire" would constitute a serious if not fatal flaw in the author's approach.

This latter proposition is not only supported by the work of de la Cova, but at least two other books which feature extensive discussion of what are clearly a Masonic conspiracies, to use a totally loaded expression; these books are not hysterical anti-Masonic rants, but rather staid, academic works of peer-reviewed scholarship.

Take for example the following paragraphs from "Texas and the Spread of That Troublesome Secessionist Spirit through the Gulf of Mexico Basin.":

Easily the most important meeting ground of filibusters, financiers, and politicians of all ethnicities and the key vehicle for the dissemination of political ideas was Freemasonry. Indeed, Freemasons played leading roles in every secessionist movement around the Gulf of Mexico (and elsewhere) from the Florida rebellion of 1810 and the Republic of Texas of 1836 to the Cuban separatist attempts of the late 1840s and early 1850s. As Antonio Rafael de la Cova has shown, the fraternity’s own ideology impelled its members to join such movements; it was their "sworn obligation" as he notes. For instance, Scottish Rite Masons attaining the ninth and tenth degrees vowed to assist "those who struggle against oppression" and in the thirty-second degree swore to become “"soldiers of freedom" and wage war against tyranny and despotism.

There was also an institutional dimension to the filibustering and separatist ventures of the Freemasons. Masonic lodges became privileged sites where members could meet one another regularly, exchange information, and organize rebellions and movements without fear of reprisal. Masons could provide introductions to other Masons occupying important posts, and they were always able to recognize each other through secret signs and rely on one another, as they swore on the Bible to "'always aid and assist all poor, distressed, worthy Master Masons' and to 'fly to his relief' upon seeing the Grand Hailing Sign of Distress." In the absence of political parties within the Spanish Empire in the 1800s and 1810s (and even after parties were established in Mexico in the 1820s), it was only natural that the more established lodges and grand lodges in Louisiana and elsewhere in the South would sponsor new lodges all around the Gulf of Mexico basin. Grand lodges of Louisiana and South Carolina chartered some of the earliest lodges in Cuba, and prominent Louisiana Masons--beginning with Stephen F. Austin of the Louisiana no. 109 Lodge--became influential colonists and politicians in Coahuila and Texas. Even the symbols employed in these insurrections and breakaway republics were of Masonic inspiration. The ubiquitous lone star--the five-pointed star that was in the symbol of the West Florida Republic, the Texas Republic, and the proposed project to liberate Cuba in 1848-49--represented the Masonic five points of fellowship. While Freemasons represented small minorities in each of the gulf provinces and colonies, they predominated in all filibustering/separatist movements during the first half of the nineteenth century. (Résendez, 198-199)

Chapter 2 of Miller's New Orleans and the Texas Revolution is dedicated to detailing the machinations of the group of Freemasons in New Orleans who financed and helped foment revolution in Texas, along with the group's links to Mexican Freemasons via Zavala. The details are stunning--addresses, dates of meetings, etc.--and leave no doubt that the Texas Revolution and the foundation of the Republic of Texas was in large part a Masonic conspiracy. That sounds fantastic, but it's a legitimate if sensational way of phrasing it.

When we recall that New Orleans politician (and Freemason) Pierre Soulé had campaigned on behalf of William Walker we edge closer to the conclusion that there was a sustained and concerted effort by Freemasons to create the Golden Circle, providing further evidence that the motivation was, as with Cuba's Havana Club, economic. As Miller concludes:

Commercial exploitation and land speculation were certainly greater forces behind any meetings with Texian representatives with New Orleans business men and capitalists.

The disturbing fact remains that slavery was an essential component of this economic system. As I suspected, the early attempts to create these republics, from West Florida to Texas to Nicaragua--in parallel (or concert) with the efforts of the KGC--was to propagate slavery out of fears that abolition in the US would eventually destroy the economic fortunes of the planters and land speculators behind the revolutionaries and filibusters.

Southerners had been eyeing Texas as an extension of the cotton kingdom since the early 1800s. Stephen F. Austin remarked in 1829 to Governor Augustin Viesca that he predicted that the Southern states would eventually secede from the United States. Ramón Musquiz, jefe politico of San Antonio de Béxar, wrote to the governor of Coahuila y Texas on March 11, 1833, discussing the affairs in Texas. He predicted that the Southern states would attempt to secede from the United States and “[t]he acquisition of Texas or its attachment to them when they make their attempt, would enlarge the territory belonging to the new government and because [of] this one acquisition or attachment, the new state would doubtless gain greater wealth than it would receive from the other states”.

...

Stephen E Austin also believed that Louisiana had a vested interest in what happened to Texas. Writing to his cousin Mary Austin Holly from New Orleans in August, 1835, Austin stated that, “It is very evident that Texas should be effectually and fully, Americanized--that is--settled by a population that will harmonize with their neighbors to the East. . . . Texas must be a slave country. It is no longer a matter of doubt. The interest of Louisiana requires that it should be. A population of fanatical abolitionists in Texas would have a very dangerous and pernicious influence on the overgrown slave population of that state. (Miller, 31-32)

"Southerners had been eyeing Texas as an extension of the cotton kingdom since the early 1800s." Likewise Cuba, Mexico itself and Central America.

Another interesting thing with this whole Golden Circle/Slave Republic filibuster scheming is it's link with the insurrections against Spain farther south. In ¡Viva la Revolución! I mentioned that the flag of Chile as having been inspired by the US flag. More strikingly, it is essentially the flag of the great State of Texas:

|

| Flag of Chile, aka La Estrella Solitaria -- "The Lone Star", 1817 |

|

| Texas Flag aka The Lone Star Flag. |

The adoption of the Chilean flag is usually attributed to José Ignacio Zenteno del Pozo y Silva, Chilean Minister of War and Navy 1817-1822 under Bernardo O'Higgins, although the actual designer is said to have been one Antonio Arcos y Arjona.

Need we add that O'Higgins and Zenteno were Freemasons and members of the clandestine Lautaro Lodge?

Likewise Poinsett, who had served past Master of Recovery Lodge #31, Greenville, SC, and was a member of Solomon's Lodge, Charleston.

As for Arcos y Arjona, at least one source claims "ses liens avec les loges maçonniques espagnoles sont connus." ("His links with Masonic Lodges are known").

After Robert Poinsett left Chile and returned to the United States, he was appointed the first U.S. ambassador to Mexico in 1825, after having served as a special envoy in 1822-23. As ambassador, he became mixed up in the country’s political turmoil and was recalled in 1830. Apparently, one reason behind his recall, which he himself requested, was the result of a Masonic dispute, with the Mexican Scottish Rite claiming he was promoting the York Rite at their expense. We'll take a closer look at this in a moment....

Poinsett was also a "lifelong" friend of Zavala, having met him in 1822 (Henson, 28). Poinsett was intimately involved in facilitating his voyage in the US to meet with investors interested in profiting from land acquisition in Texas (Henson, 46). Poinsett was in the thick of Masonic intrigues over a period of thirty years, intimately involved in three revolutions in both hemispheres of the Americas.

Poinsett may have been the first to suggest the use of the Lone Star, in Chile, but it was used in Texas about the same time. The earliest Texas Lone Star Flag was used by Dr. James Long, who led filibuster expeditions into Mexico as early as 1819. He even set up an early attempt at a Republic of Texas, which lasted a month. On a second expedition, he had more success, but was eventually forced to surrender and executed in Mexico in 1821. In these he was joined by José Félix Trespalacios. According to Edward Miller, they both met with the very same groups of merchants and capitalists (and New Orleans Freemasons) that Austin and Zavala met with some 15 years later for their more successful attempt to set up a Republic of Texas. Long and Trespalacios clearly ran in Masonic circles, but if they themselves were Freemasons, I cannot determine.

According to one website

Among his "Supreme Council" of advisers were Stephen Barker, Horatio Bigelow, John G. Burnet, Hamlin Cook, J. Child, Peter Samuel Davenport ---, Pedro Procello, John Sibley ---, W.W. Walker, and Bernardo Gutiérrez, former commander of the Republican Army of the North. In addition to Long, Vicente Tarin, former Commandant of the Second Flying Company of Alamo de Parras and anti-Spanish resistance leader in Texas, was a signatory to Dr. Long's Declaration of Independence where he is identified as "Secretary."

How many of these men were Freemasons?

As a brief aside, I should mention that in addition to these filibuster expeditions, one prior attempt to secede from Mexico was attempted by Anglo settlers about ten years before the Texas Revolution.

The Fredonian Rebellion took place between December 1826 and January 1827, led by Haden (or Hayden) and Benjamin Edwards. The rebels declared the short-lived Fredonian Republic built around the colony led by older brother Haden, who was a Freemason, but that didn't stop fellow Freemason Stephen Austin from condemning Edwards' actions and actively helped quell it by sending armed men from his colony to aid the Mexican army. Perhaps Austin feared Edwards would ruin his own plans; his correspondence indicates he felt it "premature." Interestingly, the Fredonian flag did not feature a Lone Star. A Freemason, but not the right kind?

After his defeat, the Edwards brothers fled to Louisiana, but Haden

returned to Texas during the Texas Revolution and made his home in Nacogdoches until his death, on August 14, 1849. Edwards was the first worshipful master of Milam Lodge No. 2 when it was organized in 1837, a fact that indicates his status in the Anglo leadership. Until his death he was engaged in the land business.

The filibusters were essentially mercenaries attempting to establish slave-holding republics by force. But in Mexico there was another kind of colonist called an "empresario". The empresarios were settlers who had been granted the right to form colonies in Mexico in exchange for recruiting settlers and assuming responsibility for their welfare. Many of the leaders of the Texas Revolution had been empresarios: Austin, Burnet and Zavala among them. Haden Edwards had been an empresario.

Large tracts of land were at stake and, as one can imagine, the potential for fortune lured many adventurers. In Masonic connections, pecuniary interests, and institutional development along Mexico's far north Andrés Reséndez reports that although Freemason accounted for less than ten percent of empresario-led colonists, more than half of the land grants given to empresarios were granted to Freemasons. With those kinds of numbers, it was inevitable that conflicts arose between Masonic camps. In Mexico, this was played out in the rivalry between the York and Scottish Rites. This reflected a larger conflict between centralists and federalists; the Scottish, or "escocés" favored tighter control over the colonists, including requirements made law in 1824 that they speak Spanish and practice Catholicism. "Yorkinos" favored less restrictive and less centralist policies; unrestricted immigration, religious freedom, free trade, etc.. Thus, when Poinsett petitioned for the creation of more York Rite lodges, he was, perhaps unintentionally, promoting a federalist agenda. His good friend Zavala, for example, received a land grant far larger than the usually-imposed limit.

Reséndez believes that these conflicting interests between the landed classes were the prelude to the civil war which was the Texas Revolution. In this case the fears of the escocés were borne out as a result of a less restrictive policy regarding Anglo immigration to Texas. Poinsett personally opposed slavery, but by favoring the Yorkinos he was in effect supporting the goals of slaveholders.

The aforementioned Colonization Law of 1824 provoked the Fredonian Rebellion. It is telling that Milam Lodge, led by Haden, was one of the three Lodges from which the Grand Lodge of Texas was formed in 1849; although dropped in 1858, the original Constitution affirmed that the Texas Grand Lodge were York Rite Masons. Austin, who helped suppress the rebellion, was affiliated with the Scottish Rite; his involvement thus reflects the conflict between the Rites as part of the wider conflict of competing landed interests. As the "Father of Texas" Austin clearly had no problem with revolution, he merely thought Edwards was being hastily imprudent to the point of madness. That said, the contradictory fact remains that ten years after the Edwards debacle, Austin's support for revolution was prompted by Mexico's shift from a federalist to a centralist model.

According to one history, Benjamin Edwards "was one of those who viewed the whole movement of immigrants into Texas as a prelude to ultimate annexation of the territory to the United States." He too worried if their actions might be premature. Bear in mind that this York/Scottish divide didn't reflect the situation the the United States. Nicholas A. Sterne, a friend of Sam Houston, "While still in New Orleans [had] joined the Masonic lodge, including the Scottish Rite, an affiliation of great importance to him in later years." Sterne was an active player in the Fredonian Rebellion and was arrested for smuggling arms and sentenced to death. His Masonic affiliation saved his life.

This Mexican federalist/centralist conflict parallels the underlying conflict of America's own Civil War. Ironically the Southern Jurisdiction is headquartered in Washington, D.C. and Pike, it's charismatic leader for over 30 years, is the only Confederate general honored by a statue in the capital city of the Union he fought against. Pike, incidentally, lived in New Orleans between 1853 and 1857. During the Civil War, Pike was the Confederacy's envoy to the Native American tribes of the area and he made several contact with the Creeks and Cherokees. Haden Edwards had also worked with the Creek and Cherokee Indians, to the extent that the flag he used, red and white bands emblazoned with the word "Independence", symbolized the red and the white man. The 50+ percent of land grants granted to Freemason's during Edwards' day included grants to Anglo-Americans, Mexicans and Indians.

I found an interesting text here and I'd like to quote it at some length. As I've said, I find it unlikely that some of the filibusters and impresarios weren't working in conjunction with members of the Knights of the Golden Circle. While I'd hesitate to say these filibuster expeditions were all directed by the KGC, they certainly shared the very same aims.

From its earliest roots in the Southern Rights Clubs in 1835, the Knights of the Golden Circle was to become the most powerful secret and subversive organization in the history of the United States with members in every state and territory before the end of the Civil War....

One little-known historical fact that is presented in the records from the 1860 K.G.C. convention is that the Knights had their own well-organized army in 1860, before the Civil War had even begun, so they were prepared in the event of war with the North. In May of 1860 the Knights of the Golden Circle reported a total membership of 48,000 men from the North, who supported "the constitutional rights of the South," as well as men from the South, with an army of "less than 14,000 men" and new recruits joining at a rapid rate.

Shortly before the Civil War began, the state of Texas was the greatest source of this organization's strength. Texas was home for at least thirty-two K.G.C. castles in twenty-seven counties, including the towns of San Antonio, Marshall, Canton, and Castroville. Evidence suggests that San Antonio may have served as the organization’s national headquarters for a time.

The KGC re-branded itself as the Order of American Knights in 1863 and then again as the Order of the Sons of Liberty in 1864. I wonder if ex-Knights were among the six Confederate veterans who founded the KKK in 1865? The Ku Klux Klan is believed to have taken it's name from the Greek κύκλος, meaning...."circle"!

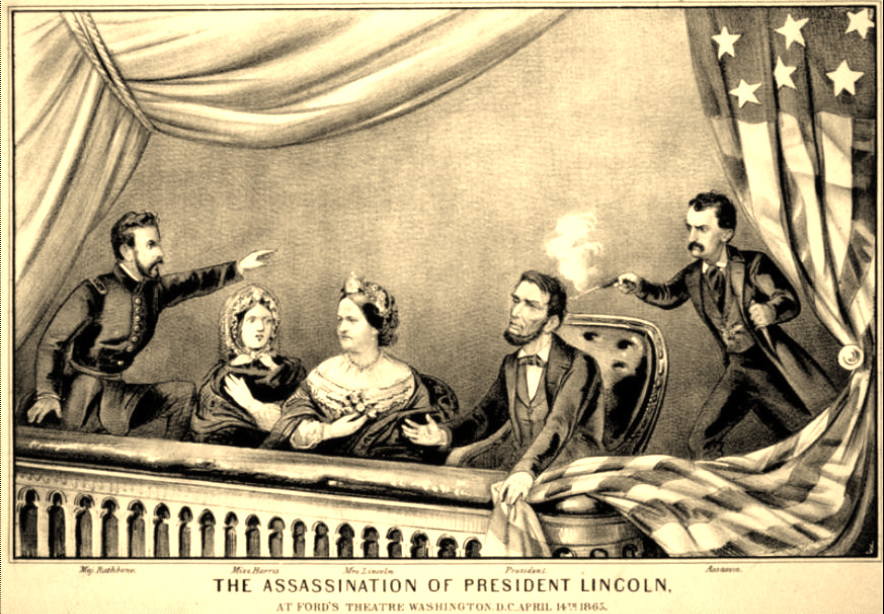

The text quoted above gives a bit of detail about their numbers and the extent of their power. Later in the war they talked of fomenting rebellion in the Old Northwest as wells as using agents to agitate for pacifism and draft riots in the North. Sam Houston is said to have been a member, as well as Jesse James. Perhaps the most sinister alleged member is John Wilkes Booth. The veracity of these claims is (perhaps) impossible to prove, but the fact is that with Houston and Booth at least, their known views correspond neatly with the stated goals of the KGC.

The Masonic character of the KGC is without doubt: three degrees, oaths, grips, hailing signs. This would suggest that some members had a familiarity with Freemasonry, at the very least. The KGC, however, unlike the Freemasons, were a secret society in the true sense of the word. Lodges don't hide their meeting places and Masons don't hide their membership. This is how we know all of the guys we've discussed were Freemasons. The Knights were actively opposing the US government during wartime. You were unlikely to see a Knight sporting a KGC ring or enamel badge on their buggy. So, we can only surmise to which extent Masons were implicated in the KGC. As to whether or not it was an outgrowth of Freemasonry itself, while some would easily jump to that conclusion, nothing I have read so far leads me to do the same.

I would expect to find large numbers, however, of Masons as members and leaders of the KGC, given the Masonic involvement in parallel filibuster expeditions in Florida, Texas and Cuba. Briefly put, the Masonic brotherhood in the South facilitated these schemes and used the cover and secret modes of recognition Freemasonry offered in order to carry out actions of questionable legality, schemes which would certainly have been frowned upon by the US government.

A lot of questions linger. Is the KGC older than 1854 or did it, as widely believed, evolve from earlier groups sympathetic to slavery and the South? Was there a central organization behind the various filibuster expeditions, or did they simply involve the same actors over a period of some decades? Wouldn't new contenders have wanted to talk to the folks who showed interest previously, or who had already tried? Was the KGC Masonic? Was Albert Pike a Knight? Was the KKK founded by ex-Knights? Was this all about land and money, or was it an ongoing series of strikes against Catholic Spain? Or both? Were the 9th and 10th degrees of the Scottish Rite, which include the obligation to assist "those who struggle against oppression" and the 32nd degree obligation to become "soldiers of freedom" against despotism subordinate to the desire to maintain a ruling class's economic privileges? Do these oaths have any value when, in addition to creating republics with Constitutional-style liberties, they also included the propagation of slavery? Does that in turn render the US constitution worthless?

The Spanish-American War is sometimes cited as the last of the filibuster wars. It certainly was a huge blow to Spain, the final nail in the imperial coffin. Three important territories acquired as a result of this war adopted flags incorporating Masonic elements in their design (Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines). Cuba may well have been the last Lone Star Republic. Many of the leaders and generals in the independence struggle were Freemasons:

"The Cuban Freemasonry movement was influenced by the principles of the French Revolution - "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity" - as well as the Masons' main guidelines: God, Reason, Virtue."

Spain had already been weakened by the wars of independence led by Freemasons in the early 19th century and Americans were eager to rid Cuba of the Spanish as the one exception to the Monroe Doctrine, formulated by President and Freemason James Monroe. "Apostle" of Cuban Independence José Marti was also a Freemason. Marti knew that he would have to defeat the Spanish, but he was also wary of US involvement, for he knew the Cubans might have to fight for independence from another colonial power, the US. Cuba was ceded to the US in the wake of the war, but the treaty was ignored by President (and Freemason) Teddy Roosevelt; Cuba was granted independence in 1902, although the US retained the right to have some measure of control over Cuban financial and foreign policy.

The Filipinos also feared falling into the clutches of another colonial power when the US entered into war against Spain in 1898. The Filipinos had already been fighting for independence for a few years at that point. The revolt against the Spanish empire had been lead by the Katipunan, a secret society whose organization and rituals were influenced by Freemasonry and whose key leadership consisted of Freemasons. The national hero of the Philippines, Freemason Andrés Bonifacio, flew a battle flag any filibuster would have gladly flown: a field of red emblazoned with a single white sun, or star, with the acronym "K.K.K." (for Kataas-taasan, Kagalang-galang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (Highest and Most Honorable Society of the Children of the Nation). They would not continue to lead the fight against the US, who basically replaced the Spanish, due to internal schisms and dissension. Their fears were not ungrounded, and the Philippines were not granted formal independence until 1946 and included one war between American occupiers and Filipino revolutionaries between 1899 and 1902.

The Spanish-American War has also been called the first of America's imperialist wars. The War inaugurated at the beginning of "America's Century" where the American economic model rose ascendant over the world. It was not the feudal agricultural model envisioned by the filibusters, the KGC and Southern economic interests, but that of the industrial North. The protection of US economic interests has played out in nearly every country in the Caribbean and Latin America. The dreams of a Golden Circle may seem far out, but American economic elites have often had their way south of the US border. Of course, this is no longer carried out under the cloak of Freemasonry but of groups, think tanks, commissions and boardrooms. None dare call it conspiracy and to be frank, there's no need when it can rightfully be referred to as "business as usual."

Further reading:

De La Cova, Rafael. "Filibusters and Freemasons: The Sworn Obligation." Journal of the Early Republic 17.1 (1997).

Denslow, William R. 10,000 Famous Freemasons. Richmond: Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply Co., Inc., 1957.

Henson, Margaret Swett. Lorenzo De Zavala: The Pragmatic Idealist. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1996.

May, Robert E. The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire, 1854-1861. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Miller, Edward L. New Orleans and the Texas Revolution. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004.

Résendez, Andréz. "Masonic connections, pecuniary interests, and institutional development along Mexico's far north." The Divine Charter: Constitutionalism and Liberalism in Nineteenth-Century Mexico. Denton: Texas State Historical Association, 2007. 109-132

Résendez, Andréz. "Texas and the Spread of That Troublesome Secessionist Spirit through the Gulf of Mexico Basin." Secession As an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements. Don H. Doyle. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010. 198-199.

Report of the Judge Advocate General on "The Order of American Knights," alias "The Sons of Liberty". A western conspiracy in aid of the Southern Rebellion. Washington, D.C.: Daily Chronicle Print, 1864.

****

.png)